TL;DR

There is too much money in the system relative to the real economy

This capital superabundance has been turbocharged post pandemic

Ultra low interest rates for a decade and money pumping by central banks have inflated assets massively

Assets all around are inflated - equity prices, private company valuations, crypto, housing etc.

The music has to end sooner than later; Inflation in consumer prices will mean inevitable rise in interest rates which might pop the bubble

One hope is that in the bubble a lot of innovation and experimentation happens; This can probably push society forward in the longer run

We should still be wary of what will be the second order societal effects when the bubble pops

Note: The below are a collection of notes I had made from various articles and reports related to this subject

*****

Sometimes it is interesting to see predictions by a consulting company turn out almost exactly right.

Bain and Company wrote a prescient article way back in 2012 called ‘A world awash in money’. Their prediction for the rest of the decade was that there will be a flood of capital or what they called ‘superabundance of capital’.

Our analysis leads us to conclude that for the balance of the decade, markets will generally continue to grapple with an environment of capital superabundance. Even with moderating financial growth in developed markets, the fundamental forces that inflated the global balance sheet since the 1980s—financial innovation, high-speed computing and reliance on leverage—are still in place. Moreover, as financial markets in China, India and other emerging economies continue to develop their own financial sectors, total global capital will expand by half again, to an estimated $900 trillion by 2020 (measured in prevailing 2010 prices and exchange rates). More than any other factor on the horizon, the self-generating momentum for capital to expand—and the sheer size the financial sector has attained—will influence the shape and tempo of global economic growth going forward.

They estimated that financial assets will balloon by the end of the decade as follows.

The prediction (including most of the numbers) has held up. Here is a recent McKinsey report that shows financial assets have raced ahead compared to the real economy

Going back to the 2012 Bain article, there are a lot of noteworthy quotes very relevant today:

Facing capital superabundance, investors are straining to find a sufficient supply of attractive productive assets to absorb it all. The sheer volume of liquidity being pumped into the markets by major central banks has sparked inflation fears.

Stockpiled with financial assets, yield-hungry investors are venturing well beyond sustainable income-producing investments in pursuit of returns that for many could prove illusory.

Given the ample spare capacity for production across the world, however, we expect that inflation will not show up in core prices in most markets but rather in asset bubbles

Capital superabundance will tip the balance of power from owners of capital to owners and creators of good ideas—wherever they can be found.

This change will not be easy. Reinforced by central banks’ unprecedented monetary easing, the plentiful supply of capital is holding interest rates at near-record lows and adding pressure on investors to find higher-yielding uses for their money. But the scramble for more promising ways to put capital to work, which is driving up asset prices, makes it difficult to identify investments that satisfy their risk-return requirements—the hurdle rate that the potential investment must clear to warrant committing capital in the first place.

But as yield-seeking capital increasingly crowds into all available asset classes, diversification will become even harder to achieve. Indeed, over the past decade the returns among assets that have traditionally been negatively correlated—equity values moving up as bond yields decline, for example—have begun to move in the same direction.

There were a few key implications called out in the report which are still being played out:

1. Persistently low interest rates

A prolonged period of capital surplus will be characterized by persistently low interest rates, high volatility and thin real rates of return. Some big institutional investors, like pension funds, will face large gaps between the returns they will need to meet payouts to beneficiaries and what markets will generate. To get into sync with these new conditions, all investors will need to ratchet down their market interest rate expectations and revise their internal investment hurdle rates and portfolio investment return targets accordingly.

2. Potential for Bubble risks

Capital superabundance will increase the frequency, intensity, size and longevity of asset bubbles. The propensity for bubbles to form will be magnified as yield-hungry investors race to pour capital into assets that show the potential to generate superior returns. Because the global financial system has grown so large relative to the underlying economy, asset values can quickly reach unsustainable levels and remain inflated for months or years…

Capital superabundance has been turbocharged in the last 2 years due to the Covid pandemic. The balance sheet of Fed has expanded drastically as a response to the Pandemic.

The interest rates were further slashed to close to zero percent (shown below)

Investors and those with obligations like Pension funds who usually invest in relatively safer bonds are now forced to chase after yield with bond price yields steadily diminishing over the past three decades

So much money that is pumped in and created has to go somewhere. And it is inflating assets across the board in an accelerated way in the last 2 years.

Goldman Sachs tracks a ‘non-profitable technology index’ which has outperformed the market index significantly last 2 years.

Even the broader market is outperforming top value investors like Warren Buffett. Below is performance of S&P 500 (ticker GSPC) vs. Berkshire Hathaway in the last few years.

2021 was also a record year for IPOs far surpassing the record set last year

We have seen companies like EV truck maker Rivian achieve a market cap of 100bn$ despite delivering only 156 vehicles so far. The Wall Street Journal called the company the ‘Government Unicorn’.

Tesla is worth 1 Trillion dollars and is worth more than the next nine automakers combined.

About 250bn$ of options value is traded on Tesla stock every single day.

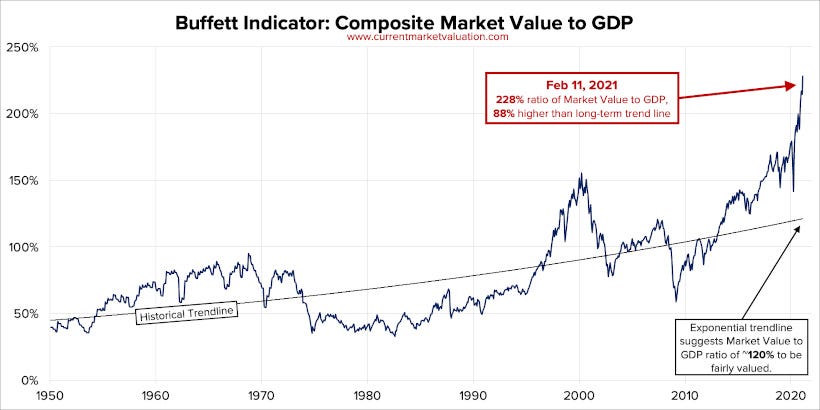

The Buffett Indicator (total market capitalization of US stocks vs. dollar value of GDP) is way higher than dot-com bubble.

There has been massive money flow in the private markets too. Below is the VC funding trends.

The number of new unicorns (private companies valued at 1bn$ or more) has accelerated in the last few quarters as seen below.

In India, there were around 37 unicorns from 2010-2020 and in 2021 alone there were 42 new unicorns.

The VC funding environment has been extremely founder friendly. Just two firms Tiger Global and Andreesen Horowitz participated in 460 deals in the first 313 days of the year - an average of 1.5 deals per day between the two! (albeit with some method to the madness).

As one top VC observed:

A lot of money is flowing into new alternative assets like Crypto. The total market cap of Crypto assets is around 2.5 Trillion dollars. Meme coins have rocketed to the moon.

The housing prices have also seen big gains albeit also because of shortage of construction.

McKinsey reports ‘net worth’ has grown much faster than GDP across countries.

But the growth in net worth has mainly come from equity valuation increases and real estate gains rather than ‘investments’.

Net worth is a claim on future income, and historically its growth has largely reflected investments of the sort that drive productivity and growth, in addition to general inflation. Over the past two decades, however, net investment as a share of GDP has been low and declining, particularly in advanced economies, contributing just 28 percent to net worth expansion. Asset price increases made up 77 percent of net worth growth.

…Net worth in the household sector grew from 4.2 times GDP in 2000 to 5.8 times GDP in 2020, exceeding net worth growth overall. Half of household net worth growth came from rising equity valuations, particularly in China, Sweden, and the United States, with another 40 percent coming from rising housing valuations.

Almost 2$ of debt have been created in the last 2 decades for $1 of net investment.

Unless there is an increase in productive deployment of capital in investments, there is likely going to be a reversion to the mean of asset prices.

There are different ways to interpret the expansion of balance sheets and net worth relative to GDP. It could mark an economic paradigm shift, or it could precede a reversion to the historical mean, softly or abruptly. Aiming at a soft rebalancing via faster GDP growth might well be the safest and most desirable option. To achieve that, redirecting capital to more productive and sustainable uses seems to be the economic imperative of our time, not only to support growth and the environment but also to protect our wealth and financial systems.

In the first view, an economic paradigm shift has occurred that makes our societies wealthier than in the past relative to GDP. In this view, global trends including aging populations, a high propensity to save among those at the upper end of the income spectrum, and the shift to greater investment in intangibles that lose their private value rapidly are potential game changers that affect the savings-investment balance. These together could lead to sustainably lower interest rates and stable expectations for the future, thereby supporting higher valuations for assets than in the past.

In the opposing view, this long period of divergence may be ending, and high asset prices could eventually revert to their long-term relationship relative to GDP, as they have in the past. Increased investment in the post-pandemic recovery, in the digital economy, or in sustainability might alter the savings-investment dynamic and put pressure on the unusually low interest rates currently in place around the world, for example. This would lead to a material decline in real estate values that have underpinned the growth in global net worth for the past two decades.

Not only is the sustainability of the expanded balance sheet in question; so too is its desirability, given some of the drivers and potential consequences of the expansion. For example, is it healthy for the economy that high house prices rather than investment in productive assets are the engine of growth, and that wealth is mostly built from price increases on existing wealth?

The smartest way forward, then, may be for decision makers to work to stabilize and reduce the balance sheet relative to GDP by growing nominal GDP. To do so, they would need to redirect capital to new productive investment in real assets and innovations that accelerate economic growth.

One problem is, the Fed will likely be caught in a Catch-22 like trap - scaling back money injection will mean asset prices will fall and since asset prices falling will lead to angst among many, the Fed will think twice about scaling back and kick the can down the road and further inflating asset prices (making the eventual pain much more severe).

What eventually happens is the inflation we see in asset prices will eventually come to the real economy too. The consumer price inflation is now at a nearly 4 decade high.

The real interest rates are negative today.

There maybe a lot of pressure for Fed in the coming year(s) to increase interest rates if inflation continues to grow at this pace. And higher interest rates will undoubtedly lead to a drop in asset prices.

And very few today even talk about all the Government debt. (what happens if interest rates rise and so does the cost of servicing this debt?)

To summarize, there is too much money in the system. There are serious second-order societal implications that we may not be able to comprehend yet when the music stops.

One hope is that bubbles are periods when investments in new technology and experimentation and innovation happen at an accelerated pace and that can move society forward in the longer run. This has been illustrated very well by Tobias Huber (excerpt below).

Yet not all bubbles are necessarily wealth- and value-destroying events. Rather, the formation of certain bubbles can be understood as an important process for innovation in various domains. As some financial bubbles deploy the financial capital necessary to fund disruptive technologies at the frontier of innovation, they are, thus, capable of accelerating breakthroughs in science, technology, and engineering. By generating positive feedback cycles of excessive enthusiasm and investments — which are essential for bootstrapping various social and technological enterprises — bubbles can be socially and economically net-beneficial. In other words, without the innovative spillover-effects of financial bubbles, many technological innovations or large-scale societal projects might never have happened.

As Perez has shown, each technological disruption is triggered by a financial bubble, which allocates excessive capital to emerging technologies. Perez has identified a regular pattern of technology-diffusions. There is an “installation” phase in which a bubble drives the installation of the new technology. This is followed by the collapse of the bubble or a crash, to which Perez refers to as the “turning point.” After this transitional phase — which occurred, for example, after the first British railway mania in the 1840s, or, more recently, after the dotcom-bubble — a second phase is unleashed: the “deployment” phase, which diffuses the new technology across economies, industries and societies. The economic exhaustion of the technological revolution and excessive financial capital, which searches for new investment opportunities, can, then, give rise to the next technological revolution.

These bubbles, which have seeded major technological innovations and disruptions, share a central dynamic: the funding of these new technologies, energy sources, or networks decouples from expectations of economic return and, correspondingly, alter the risk profiles of the economic agents participating in a speculative mania. Irrespective of quantifiable financial returns and economic values, bubbles mobilize the financial capital needed to develop new transformative technologies. As the venture capitalist and economist William Janeway has shown, bubbles are necessarily wasteful as technological innovations require “inefficient” trial-and-error experimentation.

There is a lot of experimentation and innovation happening in Crypto, Fintech, Climate Tech, EVs, Energy, EdTech, Remote Work, AI and Software in general which will move society forward. The future possibly looks optimistic but there may be a lot of ‘correction’ and ambiguity while we get there.